On Saturday 4th February 1888 troops fired into thousands of Rio Tinto miners and local farmers demonstrating in the then British-owned mining village of Rio Tinto in Huelva province. Known as “En el tiempo de los tiros” (In the time of the shots/shootings), the official casualty figure was 48 people killed or wounded but it is estimated to be many more as family members and friends carried off bodies and surreptitiously concealed them to prevent possible reprisals.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay.

However, after its purchase in 1873, the British-registered Rio Tinto Company had turned the loss making mine into a profitable enterprise and the greatest mining centre in the world by introducing open cast mining. Open-air calcination was the only practical method of treating the large quantities of ore raised until the less-hazardous alternative process of cementation was fully developed.

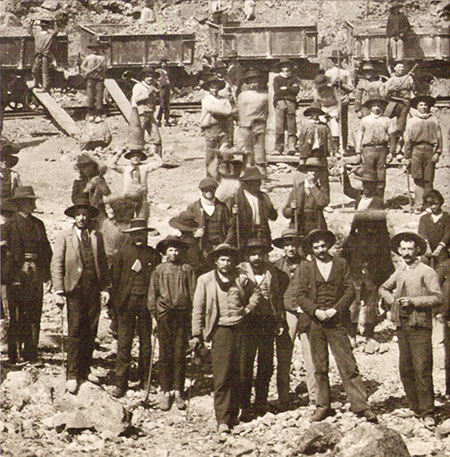

Although the smoke problem provided focus, hostility resulted from a web of circumstances. Rapid expansion of the mine’s workforce from 1000 to 9000 caused overcrowding. The newcomers, recruited from across Spain and Portugal, overflowed into surrounding mining and agricultural villages, straining established infrastructures and social fabrics, and arousing local resentment.

Most of the new arrivals were young unmarried men and excessive drinking, gambling and brothels resulted in riots, fights and stabbings. During the autumn of 1883 there was an average of one murder a week. A year later the company, overriding protests, bought and demolished the bullring – a focal point of crime and violence.

Hugh McKay Matheson, the inspiration behind the Rio Tinto Company’s formation, and its first Chairman, sought solutions. Enigmatic, successful entrepreneur, banker and benevolent despot, he was also an intensely devout Scottish Presbyterian. He initiated a housing programme and in villages where employees lived set up workmen’s clubs, with cheap wine, free recreational facilities and elected committees and he also personally funded two schools, its equipment and two teachers. A new hospital and village surgeries were established to cater for workers, their families and the widows and orphans of former employees.

Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

There were strikes and dismissal of political agitators. Better paid and with better facilities than their Spanish equivalents, workers nonetheless demanded improved wages, housing, welfare services and social amenities and the abolition of compulsory contributions to the company’s health services. They also wanted an indemnity policy to replace non-obligatory ex gratia payments for injuries due to accidents and pensions for dependents of those killed at work.

Poor labour management and self-imposed isolation of the comfortably off British managers aggravated a deeply resented disciplinary code enforced by a strict dismissals policy. The mostly Scottish Presbyterian staff lived in Bella Vista, an architecturally replicated British village. With its own Kirk-like chapel and recreation club, it was surrounded by walls, gates and security guards.

It has been claimed that some of the crowd had rifles and hurled stones. And it is not known who, if anyone, gave the command for the troops to fire. What is known however is that the anarchist instigator of the protests did not die the hero’s death depicted in the film “El Corazón de la Tierra” (The Heart of the Earth). He escaped from the scene of butchery on horseback and later crossed into Portugal.