- Details

-

Published: Tuesday, 26 March 2013 02:53

-

Written by Tom Dooley

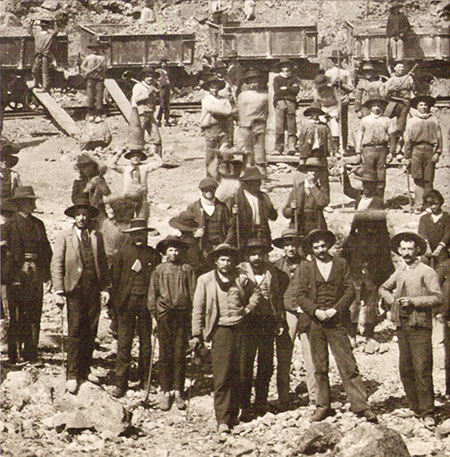

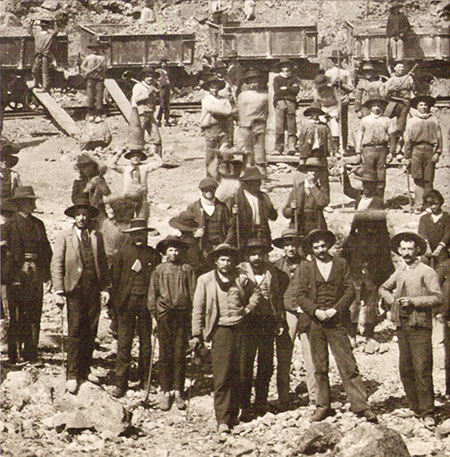

On Saturday 4th February 1888 troops fired into thousands of Rio Tinto miners and local farmers demonstrating in the then British-owned mining village of Rio Tinto in Huelva province. Known as “En el tiempo de los tiros” (In the time of the shots/shootings), the official casualty figure was 48 people killed or wounded but it is estimated to be many more as family members and friends carried off bodies and surreptitiously concealed them to prevent possible reprisals.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay.

However, after its purchase in 1873, the British-registered Rio Tinto Company had turned the loss making mine into a profitable enterprise and the greatest mining centre in the world by introducing open cast mining. Open-air calcination was the only practical method of treating the large quantities of ore raised until the less-hazardous alternative process of cementation was fully developed.

Although the smoke problem provided focus, hostility resulted from a web of circumstances. Rapid expansion of the mine’s workforce from 1000 to 9000 caused overcrowding. The newcomers, recruited from across Spain and Portugal, overflowed into surrounding mining and agricultural villages, straining established infrastructures and social fabrics, and arousing local resentment.

Most of the new arrivals were young unmarried men and excessive drinking, gambling and brothels resulted in riots, fights and stabbings. During the autumn of 1883 there was an average of one murder a week. A year later the company, overriding protests, bought and demolished the bullring – a focal point of crime and violence.

Hugh McKay Matheson, the inspiration behind the Rio Tinto Company’s formation, and its first Chairman, sought solutions. Enigmatic, successful entrepreneur, banker and benevolent despot, he was also an intensely devout Scottish Presbyterian. He initiated a housing programme and in villages where employees lived set up workmen’s clubs, with cheap wine, free recreational facilities and elected committees and he also personally funded two schools, its equipment and two teachers. A new hospital and village surgeries were established to cater for workers, their families and the widows and orphans of former employees.

Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

There were strikes and dismissal of political agitators. Better paid and with better facilities than their Spanish equivalents, workers nonetheless demanded improved wages, housing, welfare services and social amenities and the abolition of compulsory contributions to the company’s health services. They also wanted an indemnity policy to replace non-obligatory ex gratia payments for injuries due to accidents and pensions for dependents of those killed at work.

Poor labour management and self-imposed isolation of the comfortably off British managers aggravated a deeply resented disciplinary code enforced by a strict dismissals policy. The mostly Scottish Presbyterian staff lived in Bella Vista, an architecturally replicated British village. With its own Kirk-like chapel and recreation club, it was surrounded by walls, gates and security guards.

It has been claimed that some of the crowd had rifles and hurled stones. And it is not known who, if anyone, gave the command for the troops to fire. What is known however is that the anarchist instigator of the protests did not die the hero’s death depicted in the film “El Corazón de la Tierra” (The Heart of the Earth). He escaped from the scene of butchery on horseback and later crossed into Portugal.

- Details

-

Published: Monday, 01 July 2013 23:29

-

Written by Tom Dooley

Although city blocks peek over its walls, Huelva´s Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (Our Lady of Solitude) cemetery is serene and beautifully maintained. The cool shadow of a lone cypress tree is draped over the grave of ‘The Man Who Never Was’, identified by an amateur historian as Glyndwr Michael, a vagrant Welsh alcoholic who ingested rat poisoning and died of chemical pneumonia.

But it has since been claimed that he was another man - the victim of a fatal accident onboard a Royal Navy aircraft carrier. Because dense secrecy surrounded the real identity of ‘Major William Martin’ it retains an enduring and beguiling hint of mystery.

Also puzzling is why he was not buried in the adjacent cementerio británico (British cemetery). It was the first place in which I searched for his grave two years ago but a wild and thick tangle of tall vegetation obscured graves and made exploration difficult. Intrigued by the little I was able to discover I made a second visit earlier this year. There had been an attempt to tame the rampaging undergrowth and although now permanently locked-up and badly neglected, a straggle of surviving tree and shrub species suggest the cemetery was once well cared for.

The partial clearance enabled me to discover the military gravestones of two airmen, one British and the other Australian. Both died on the 19th April 1942. One was 21 years of age and, according to an inscription, ‘for honour, liberty and truth he sacrificed his glorious youth’. The other was 27 years of age. The headstones appear to be of the standard War Graves Commission type, an organisation which usually preserves war graves in immaculate condition. But these burial places had long been abandoned to the whims of nature and vandals.

I wondered who these young men were. Where had they come from? How had they died? And why were they buried in a Huelva cemetery? It is ironic that they share their last resting places with those of Germans who had lived and worked harmoniously alongside Britons. As well as the graves of Britons, and their children, who died in the service of the Rio Tinto Mining Company, several bear German names as there was a strong German connection to the mining company.

Someone had placed artificial flowers on the airmen’s headstones. And on each occasion I have visited the grave of ‘The Man Who Never Was’ a bunch of artificial flowers has been replaced with new ones. Cemetery attendants could only tell me that the mysterious visitor is a woman. What, I asked myself, has inspired this touching display of compassion towards long-dead strangers?

On the wall behind these graves is a plaque commemorating a Royal Navy sailor who died on 14th December 1918 aged 24 - a futile token of remembrance to one more forgotten victim.

On entering or leaving the British cemetery, it is easy to walk pass the bullet-scarred exterior of the gates and walls, also lightly daubed with faded political graffiti, without recognising them as tangible and moving evidence of Huelva province’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Against these walls, between 1936 and 1941, hundreds of republican sympathisers and activists from across the province, many whose identity remain a mystery, were executed by firing squads.

The executions followed the defeat of the republican forces in Huelva. From the start of the war in mainland Spain on 18 July until19 September 1936 when the province was completely subdued and occupied by nationalist forces, Huelva was ensnared in a gruesome spiral of violence.

Miners throughout the province mobilized in defence of the republican government’s cause. At Rio Tinto, La Zarza and Corrales they converted vehicles into armoured cars and made grenades and other accoutrements of war. A column of armed Rio Tinto miners on their way to recapture Sevilla were routed. Twenty Five were killed, and most of the rest wounded or taken prisoner. Two truckloads of Tharsis miners, also headed for Sevilla, failed to arrive due to a muddle and returned home in disarray. Soon after, two Royal Navy destroyers evacuated British women and children to Gibraltar.

In Huelva city a convent and church were set ablaze and the houses of Rio Tinto Spanish staff dynamited. Right-wing prisoners held in coal hulks in the harbour were being put to death up until the time nationalist forces seized the town on 29 July when the army, in its turn, immediately began trying and executing republicans.

Elsewhere in the province churches were ransacked and burned and middle class houses destroyed. In one incident 22 people died in the flames or were shot trying to escape. An attempt by miners to capture the Civil Guards barracks at Tharsis was driven off. Nationalist forces entered the village the following day, imprisoning 280 miners. At about the same time Corrales was captured and more arrests made. Executions of republicans, including the mayor of Tharsis, began at once.

At Valverde del Camino Rio Tinto miners attacked a temporary army base. Forty of them were killed, many more wounded and the attack abandoned. Following five days of heavy aerial, artillery and mortar bombardment, the defenders of the Rio Tinto mines surrendered to nationalist forces on 26 August.

With the collapse of republican resistance, the army exacted a bloody vengeance and were determined to eradicate any potential republican resurgence. No village in the province, however small, was exempt from courts martial and summary executions. Day after day there were arrests. Men at work in the mines or workshops were taken in to custody and executed.

According to the book ‘La Guerra Civil en Huelva’ (The Civil War in Huelva) published in 1996, executions exceeded 5,400, the victims being women, students, labourers and business owners among others, whose ages ranged from 16 through to the late 60's. Many more died in the provincial prison or while fighting.

In the cemetery office the names of those shot against the wall of the British cemetery are recorded in several disintegrating hard-backed exercise books. Dusty and held together with brown paper tape they indicate, in fading ink, the causes of death as being, for example, ‘haemorrhage’ or ‘tuberculosis’. They also show that the victims were buried in an unmarked common grave in the Spanish cemetery.

A simple but prominent and dignified memorial has since been erected on the site. Tall cypress trees enclose it and a tablet, which seems to erupt from the Andalucian soil, bears the inscription “El Ayuntamiento de Huelva. A los que Murieron por la libertad, 1936-1941” (‘The City Council of Huelva. To those who died for freedom, 1936-1941’).

The war still has the power to arouse and drive emotions deep enough to propel foreigners and Spaniards alike into passionate arguments for or against the republican or nationalist causes. But standing alone in the penetrating stillness of the graveyard and with the lengthening March shadows closing around me, definitive argument dissolved under an overwhelming and indefinable sense of how utterly mysterious life is. The often quoted words of John Donne, the 17th century English poet, came unsummoned to mind: “… any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

- Details

-

Published: Monday, 25 February 2013 21:29

-

Written by Tom Dooley

I waited as the sun burned through an early morning mist to gradually uncover the abandoned Tharsis mine - a desolate and mysterious place. In the uncanny stillness it was difficult to imagine that it was once the most profitable copper mine in the world and that it had, along with the Rio Tinto mine, dominated the Province of Huelva's economy.

Workers had once swarmed over the enormous open-cast excavations and sweated in the decaying labyrinthine system of tunnels and shafts. Amid the noise, bustle, clank of machinery and roar of engines, heaps of ore roasted in the open-air had released great floating and poisonous sulphurous clouds that destroyed vegetation, corroded metal fittings and attacked lungs.

Now there is silence. A green mantle covers the once widely disfigured landscape but the scars left behind are dramatic and strangely beautiful. Huge open pits expose inners of greens, blues, greys, browns and reds. And the craters, with their darkly polluted waters, are streaked in a myriad of wonderfully startling patterns.

Now there is silence. A green mantle covers the once widely disfigured landscape but the scars left behind are dramatic and strangely beautiful. Huge open pits expose inners of greens, blues, greys, browns and reds. And the craters, with their darkly polluted waters, are streaked in a myriad of wonderfully startling patterns.

Not worked since Roman times, a French company made a failed attempt to exploit the mines at Tharsis and La Zarza in the 1850s. They were then taken over by The Tharsis Sulphur and Copper Company Limited in 1866. Incorporated in Edinburgh in the same year, and with its head office in Glasgow, a Scot, Charles Tennant (later Sir Charles), was the company's principle founder and first chairman. Representative of the visionary entrepreneurship of a Victorian Britain at the zenith of its imperial, industrial and economic power, he successfully headed the Tharsis Company in its risky venture by a skilful combination of capital, railway construction and commercial courage.

Packhorses, mules and carts were replaced by around 50 kilometres of railway connecting Tharsis with Corrales where a new pier with modern docking facilities greatly reduced turn about time of costly ore-carrying steam ships. By 1871 Tharsis and Corrales were linked by electric telegraph. When the principle mining effort was transferred to La Zarza in 1888, a further 30-odd kilometres of railway was constructed, joining it to Tharsis and Corrales.

Wasteful small scale and underground working was superseded by open-cast mining. This also simplified supervision and labour costs and eased recruitment by greatly reducing the need for traditional mining skills. Exploited primarily for its sulphur and copper content, gold, silver and the iron residue were also extracted from the mined ore and added to the company's profitability.

Two new communities at the Tharsis and La Zarza mines and a smaller settlement at the railway terminal and pier in Corrales were created with a total population of about 8000 men, women and children. The 50 or so British managers, mostly Scots raised in the self-help Presbyterian tradition, enforced strict discipline and represented a culture that was alien to that of the traditional, catholic and largely illiterate workforce. A colonial style segregation and paternalism intensified the company's difficulties in an increasingly volatile environment.

Two new communities at the Tharsis and La Zarza mines and a smaller settlement at the railway terminal and pier in Corrales were created with a total population of about 8000 men, women and children. The 50 or so British managers, mostly Scots raised in the self-help Presbyterian tradition, enforced strict discipline and represented a culture that was alien to that of the traditional, catholic and largely illiterate workforce. A colonial style segregation and paternalism intensified the company's difficulties in an increasingly volatile environment.

When the Tharsis mine showed signs of copper exhaustion in the 1890s it was decided to invest heavily in modernising and developing the Tharsis and La Zarza lodes for sulphur extraction only rather than close them or seek new mining opportunities. But in the 1900s there were two market-disrupting world wars, a major inter-war depression, worker militancy and strikes, the Spanish Civil War with its nationalism and political instability, fluctuating sulphur markets, the rise of new and competitive sulphur sources, and the consolidation in Spain of a system of economic control.

In the 1960s Spanish sensitivity to economic exploitation by foreign interests added to the company's uncertainties. It was subsequently sold to Campañia Española de Minas de Tharsis SAL, a Spanish company, and later passed to Nueva Tharsis SAL, a labour company created in 1996. It soon ceased production.

Wandering through the derelict buildings and deserted rail terminal is an eerie experience. As though hastily abandoned in the face of sudden catastrophe, documents lie on desks or are scattered over floors, stained brown by rain seeping through rotting roofs. Hoppers, silently rusting away, still wait for the loads of ore on conveyer belts now frozen into ghostly stillness. And British-built locomotives, and massive 'Terex' haulers with wheels twice as tall as a man, slowly disintegrate under Andalucia's harsh summer sun and cold winter rain.

In the nearby village cemetery is a simple and much-weathered memorial. In barely decipherable words it reads 'Lawrence Gould Down died at Tharsis mines 22 November 1878 age 29 years'. It was the only British grave I could find.

Stretches of the company's railway track between the mines and Corrales remain intact. In Corrales the pier is in a dangerous state of collapse. Its junction box/control tower still stands but it is dilapidated and inaccessible. Of the terminal with its railway tracks, yards, workshops, garage, stores, crushing plants and civil guards' barracks, only a crumbling building with its chimneystack and the railway station survive.

Stretches of the company's railway track between the mines and Corrales remain intact. In Corrales the pier is in a dangerous state of collapse. Its junction box/control tower still stands but it is dilapidated and inaccessible. Of the terminal with its railway tracks, yards, workshops, garage, stores, crushing plants and civil guards' barracks, only a crumbling building with its chimneystack and the railway station survive.

But the 1920s station has been carefully restored. And the beautifully reinstated and again functioning 'Teatro Cinema Corrales', originally opened in 1954 by H P Rutherford II, a Scot and the then Tharsis managing director and chairman, is a reminder of the company's British connection. So also is the Casino Minero de Corrales, built in 1918 as a cultural and recreation centre and located in Plaza Rutherford.

However, this may not be the end of the Tharsis story. In a joint venture with Nueva Tharsis SAL in 1997, the Irish company Ormonde Mining plc evaluated unexplored copper, gold and silver resources at La Zarza mine and in 2004 commenced preliminary drilling with the objective of establishing the viability of future mining operations.

- Details

-

Published: Tuesday, 26 March 2013 13:57

-

Written by Tom Dooley

Because of the absolute power he wielded autocratically when appointed general manager of the Rio Tinto mines in 1908, Walter Browning, a fluent Spanish speaker, became known as ‘el rey de Huelva’ (the King of Huelva). Spanish cartoons reflected the image, one describing him as ‘su majestad Riotinto’ (his Rio Tinto Majesty) and depicting him as a giant with two pygmies, the prime minister and a judge, in tow. Characterised by an explosive energy, he was also known as ‘el terremoto’ (the earthquake) and admired as ‘mucho hombre’ (all man) out of respect for his skilled horsemanship and iron will.

Spanish cartoons reflected the image, one describing him as ‘su majestad Riotinto’ (his Rio Tinto Majesty) and depicting him as a giant with two pygmies, the prime minister and a judge, in tow. Characterised by an explosive energy, he was also known as ‘el terremoto’ (the earthquake) and admired as ‘mucho hombre’ (all man) out of respect for his skilled horsemanship and iron will.

Experience as a lone gold prospector in Mexico and as the general manager of a copper mine, moulded his personality. An isolated life, frequently living only on what he could shoot and having to fight off attacks by hostile Indians fostered a confident self-reliance and an expertise in pistol and rifle.

The ‘kingdom’ he inherited had been purchased by an international consortium and forged by Hugh Matheson, the Rio Tinto Company’s principal founder and first chairman. A London-based banker, Matheson combined business acumen and a supreme confidence in the engineering prowess of Victorian Britain with a certainty that God was guiding him.

From the Western Highlands of Scotland, he was a devout Presbyterian. An austere teetotaller, church going and charitable, he worked among the London poor at night. During his chairmanship welfare facilities were considerably improved at Rio Tinto and schools built at his own as well as company expense, primarily to improve literacy and enable bible reading.

Under his leadership, the company became the greatest mining centre in the world. At the time of his death in 1898, Hugh Matheson was one of most powerful men in the economic life of Spain. The Rio Tinto Company was the biggest and most heavily capitalised commercial organisation in the country. It was the largest single employer of labour and provider of social services, paid substantial taxes and spearheaded the transformation of Huelva from village into industrial city.

Browning therefore ascended ‘the throne’ when the Rio Tinto Company exercised a powerful influence nationally and effectively controlled much of the political and economic life in Huelva province. He held court in the Casa Grande (Big House) in Bella Vista (Beautiful View), a replica British village in which about 120 mostly Scottish Presbyterian families lived in rigid segregation from the Spanish. Matheson had appointed a Presbyterian minister and later built a church resembling a Scottish Kirk in which he, as a Presbyterian lay-preacher, had sometimes conducted services and given sermons. The church is now derelict. Covered in graffiti, locked and boarded up, it is a poignant reminder of lives passed in a foreign land.

Life for the British centred on the club Inglés (English club) in Bella Vista where a photograph of Browning still hangs along with those of other past general managers. Entering the club today is to pass in to a vault of moribund memories fondly cared for by its Spanish inheritors. The bar entrance still bears a ‘Men Only’ brass plaque in English. Its wood-panelled walls are hung with prints of Royal Navy warships and in the hall cum theatre is preserved the Rio Tinto Company’s Union Jack and a display of silver cups and trophies – the relics of very British games. The walls are adorned with British cartoons and pictures.

A few minutes walk away, past a solitary and forgotten memorial to Rio Tinto employees who served in the Great War, is Atalaya, excavated in 1907 and exploited under Browning. It is one of the world’s largest open cast mines and is a stunning sight. Dazzling with colour, it dwarves the buildings that hug its rim. Rail tracks, part of a 300 kilometre system blasted and cut through difficult terrain, once spiralled to the bottom where, just discernible, is a rusting locomotive. It was not too fanciful to believe that I was looking into el Corazón de la Tierra (‘The Heart of the Earth’ – a novel by the Riotinto writer Juan Cobos Wilkins and adapted for cinema by Huelva director Antonio Cuadri).

Medical and welfare services continued to improve under ‘the king’. A new hospital, now the mining museum in Minas de Riotinto, was built in 1927 and in Huelva the Barrio de Reina Victoria, architecturally a piece of Britain transported to Spain, was started in 1916 to house the company’s Spanish workers.

Huelva’s Gran Teatro, inaugurated in 1923, is symbolic of the regional economic development generated by the Rio Tinto mines under Browning. He also initiated a scheme to assess the damage done to surrounding land and farms by sulphur fumes. The first eucalyptus trees were planted on mine property, a company forester employed, the large scale planting of pine, oak and cork trees recommended and pasture farming introduced.

But Browning ruled during a period of tumultuous change. The workforce expanded to almost 17000 and he wrestled with the consequences of inter-union and political turmoil as well as an anti-British movement during the First World War when he created an unofficial counter-intelligence network to track German and Bolshevik funds.

The longest series of strikes in the history of the mines occurred in 1920 with bitter conflicts during the early months of 1921. There were frequent stoppages with violence, deaths and the destruction of company property reminiscent of the riots of 1888 when troops had fired into a mob of miners and villagers, killing or wounding 48, although legend puts the deaths at between 100 and 200.

Daily, Browning personally led blacklegs through striking workers to the Rio Tinto Company pier in Huelva. Today the pier has been carefully restored and though it still juts aggressively into the Rio Odiel, it stirs up images remote from the acrimonious past. I walked it on a bright but breezy March morning. In contrast to the heady days when queues of steamships awaited loads of ore and locomotives trailing a string of hoppers rattled noisily back and fourth, I could hear only the soothing sound of water lapping against the pylons. The pier was tranquil and deserted except for three lads fishing from the end.

Browning’s ‘reign’ ended in 1927 when, having discovered that he had ‘lived like a king’ at company expense, he was asked by the chairman to resign immediately. He died in Kent, England in 1943 aged 77 years.

It was an unexpectedly peaceful end to the life of a man against whom there were at least four assassination attempts while he was at Rio Tinto. Always heavily armed and with a bodyguard, tradition has it that he carried a Winchester repeating rifle with a bullet in the breach and kept half-cocked ready for action. On his right hip and slung low was a revolver he had used in Mexico. At times of industrial trouble he wore a second one. And inside his jacket he also concealed an automatic pistol.

In 1954 the Rio Tinto Company was sold to Compañia Española de Minas de Rio-Tinto SA, a Spanish consortium. Today the Riotinto mines have ceased production but the brooding stillness of a haunting landscape still evokes a sense of wonder at the vastness of Browning’s ‘kingdom’.

In 1954 the Rio Tinto Company was sold to Compañia Española de Minas de Rio-Tinto SA, a Spanish consortium. Today the Riotinto mines have ceased production but the brooding stillness of a haunting landscape still evokes a sense of wonder at the vastness of Browning’s ‘kingdom’.

A ride in the tourist train, swaying and rattling through a kaleidoscopic panorama of strangely sculptured and multicoloured valleys, is like a journey on another planet. The brilliant blues and greens of copper-stained earth mix with the reds of metal bearing rocks oxidised over millions of years. And the ominous blood-red water of the Rio Tinto slices a path through a scattering of derelict buildings, locomotives and machinery.

The British have gone, leaving behind their dead in the small cemetery in Bella Vista. It is a sad place. Graves ravaged by vandals, time and weather drown under waves of vegetation. And buildings constructed and once occupied by the Rio Tinto Company in the nearby village of Minas de Riotinto are now put to other uses.

Of the several railway stations built by the company, the one at Zalamea la Real, with its spectacular views of the village below, is intact but closed up. And at San Juan del Puerto the former station on the edge of the marshes has been restored. Estacíon de Sevilla, the neo-Moorish style RENFE station in Huelva, was built by the company in 1880.

Also in Huelva Casa Colon, erected in 1883 as a luxury hotel but sold to the Rio Tinto Company in 1892 as offices, housing and a recreation centre for mine staff, is now used as a conference centre, exhibition rooms and municipal offices. And Punta Umbria owes its origins to the Rio Tinto Company who chose it as the site on which to build a sanatorium for British staff. By 1892 it had largely become a company weekend and holiday resort. Today a couple of the colonial-style bungalows remain in this now very Spanish resort, empty and spectral reminders that once there was a British ‘King of Huelva’.

- Details

-

Published: Monday, 01 July 2013 23:29

-

Written by Tom Dooley

Completed in 1889 and originally owned by the British Zafra-Huelva Railway Company, the 185-kilometre Huelva to Zafra railway, with its 19 bridges and 18 tunnels, provides passengers with an enchanting ride through Huelva province’s spectacularly changing panorama as well as a brush with its history.

Skirting the Odiel Salt Marshes natural park, the train passes Gibraleón’s traditional-style Our Lady of the Olive cooperative building, founded more than 60 years ago. In late spring or early summer, meadows of ripening sunflowers or young cereal plants slip by and a snaking climb into the mountains begins. The River Odiel soon appears a long way below the first viaduct encountered.

Occasionally slowing to around 20 kilometres an hour, the train dips in and out of sheer-sided cuttings of black slate and multicoloured rock or emerges from gloomy tunnels into bursts of sunlight. It passes through boulder-littered barren stretches of ground and a hilly terrain thickly covered in thyme and cistus scrub. After the winter rains there is a sometimes-dense scattering of purple, yellow, pink, and white rockrose shrubs, scarlet poppies and other wild flowers. Networks of trails zigzag through the hills and goatherds scamper over the railway track.

The landscape is interspersed with mixed forest or plantations of eucalyptus, harvested for paper pulp, and coniferous trees used as timber. Orange groves, olive trees and hill terraces give way to gentler, rolling hills and valleys of mixed pasture and woodland dominated by holm oak. There are grazing sheep and cattle and, with luck, deer can be sighted breaking cover or an eagle may glide into view. Other birds, too swift to identify, vanish in scintillating explosions of colour.

Ragged silhouettes of distant mountains and skeletal outlines of villages riding on gentle swells of ground materialize then disappear. Isolated farmhouses are glimpsed as bright flashes behind cypress and other garden trees while fleeting white villages gleam in a world splashed with the sombre grey of derelict stone farm buildings and ubiquitous stonewalls.

Passing through Los Milanos, the strikingly prominent dome and tower of Calañas’s 16th-17th century parish church of Santa Maria de Gracia can be seen through the carriage window. It is said that Roderick, the last king of the Visigoths killed in battle with the invading Moors in 711, is buried in Sotiel Coronado, just eight kilometres away.

Although the railway was designed for public use, for some small mining concerns it was the only means of transporting their ore, so they built branch lines connecting with it at the next two stations of El Tamujoso and Valdelamusa. The mines have long since been abandoned and the branch lines dismantled but there are crumbling reminders of those industrially active days. However, the nearby Aguas Teñidas mine has been re-opened and the first copper concentrates recovered in May this year. Valdelamusa may therefore again become a dynamic mining terminal.

Before entering Jubago-Gararoza black Iberian pigs, from which the famed mountain-cured ham (jamón serrano) is produced, can be seen feeding on holm oak acorns, their main diet. The streets on either side of the station are lined with sausage and ham factories or retail outlets as the very best jamón serrano is considered to come from Jubago.

On approaching Cumbres Mayores, its 13th -14th century castle, standing out darkly against the red-tiled roof and white-walled houses abutting it, can be seen in the distance. It was constructed along with others including the one at Fregenal de la Sierra, after the expulsion of the Moors, as a defence against military incursions by the Portuguese.

Fregenal de la Sierra is the first stop after crossing into Extremadura’s Badajoz province. At present, due to engineering works, and on Sunday’s only, there is an approximate two-hour interval before the return journey from Fregenal to Huelva. This allows time for a visit to the pretty and historic village. The bullring inside the ramparts of the 13th century castle presents an intriguing configuration and the evocative ruins of the 17th century Jesuits College stirs the imagination.

With just a sprinkling of passengers and a low volume of commercial traffic, the railway faced possible closure. But in 2006, when I undertook the journey, a major upgrading plan to rescue what is regarded by some travel-writers as one of the most beautiful railway journeys in Europe was approved and has since been completed.

- Details

-

Published: Saturday, 09 March 2013 13:35

-

Written by Karen Brimmer

Spring is possibly the best time to experience the beautiful countryside that surrounds us here in Ayamonte.The temperature is neither too hot nor too cold. And there is always something to see whether you are interested in birds, flowers, country living or history. In this article, I will just give you a flavour of what we have on our doorstep.

The spring flowers are just starting to put on their annual display. The first sign of spring is the Bermuda Buttercup, patches of bright yellow in unexpected corners. The almond blossom came very early this year and is now over. But you cannot fail to notice the delicate white flowers of the cistus or rockrose, but try not to get too close to the waxy leaves. The aromatic resin from the leaves is used by the perfumery industry. Asphodels are just coming into their prime and look closer for wild irises and both purple and yellow lupins.

The spring flowers are just starting to put on their annual display. The first sign of spring is the Bermuda Buttercup, patches of bright yellow in unexpected corners. The almond blossom came very early this year and is now over. But you cannot fail to notice the delicate white flowers of the cistus or rockrose, but try not to get too close to the waxy leaves. The aromatic resin from the leaves is used by the perfumery industry. Asphodels are just coming into their prime and look closer for wild irises and both purple and yellow lupins.

The summer birds are returning, and we have recently spotted swallows and avocets. The marismas (marshes) are a bird watchers paradise. Even if you don’t consider yourself a twitcher, take along a pair of binoculars to watch the sanderlings antics, scurrying along the water’s edge. For a wader, they appear not to like getting their feet wet!

Many of the country houses have kitchen gardens. In fact since’ la crisis’, there are many more in odd patches of fields and gardens. If you show an interest it is not unusual to be offered some tomatoes or oranges. And they are delicious, freshly picked. You may also notice locals gathering herbs or, recently, wild asparagus in the meadows. Soon, our neighbours will be out early each morning to collect caracoles (snails) in the nearby common land.

For the history buffs, there is evidence of wells, irrigation systems, salt pans, lime kilns, mills, and dolmens. It’s amazing to remember that some of the processes still being used today are essentially the same as those used by the Romans and Arabs.

Well, this is just a snapshot of what the surrounding area can offer as an added extra during your walk. Enjoy!

- Details

-

Published: Monday, 11 March 2013 22:20

-

Written by Bryony Collins

Two friends from Norwich arrived this weekend. They have already visited several times and been introduced to both the great food of this area and the numerous places of interest within a short drive of Ayamonte. This time we have decided to do a road trip to Granada, stopping off for a couple of nights in Cordoba and hopefully, when reading about our trip, more of you will be enticed to explore farther afield in this beautiful part of Spain that I now call home.

The first leg of the trip (Ayamonte to Sevilla) I have made several times but I never cease to enjoy the landscape. It begins with Umbrella Pines, Orange Groves and fields of Strawberries, then as you near Sevilla it changes to Olive Groves. Apart from the obvious detours you can also make en route there are a couple of items I have found particularly interesting. The first is the Ines Rosales Factory. In 1910 Ines Rosales began making tortas de aceite by hand and selling them at the railway station. Unable to keep up with demand she employed local women to help make them and today they are still made by hand using the same recipe and then individually wrapped. They are delicious on there own or with accompaniments such as cheese and fig spread. The second item is the Solar Power Station (known as PS10) which is situated just after the Mercadona Distribution Centre.

The first leg of the trip (Ayamonte to Sevilla) I have made several times but I never cease to enjoy the landscape. It begins with Umbrella Pines, Orange Groves and fields of Strawberries, then as you near Sevilla it changes to Olive Groves. Apart from the obvious detours you can also make en route there are a couple of items I have found particularly interesting. The first is the Ines Rosales Factory. In 1910 Ines Rosales began making tortas de aceite by hand and selling them at the railway station. Unable to keep up with demand she employed local women to help make them and today they are still made by hand using the same recipe and then individually wrapped. They are delicious on there own or with accompaniments such as cheese and fig spread. The second item is the Solar Power Station (known as PS10) which is situated just after the Mercadona Distribution Centre.

From Sevilla to Cordoba the landscape changes once again to gently rolling, arable farm land which has a very 'Spanish' feel to it. Cordoba itself is a lovely city, compact and very welcoming with a host of good restaurants. The Mesquita, of course, is top of the list of places to visit and just wandering round you could easily loose track of time and almost feel as though you have been transported back to the 8th Century. Other equally interesting places to visit are the Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos with its tranquil gardens and fountains, the Juderia and, if you happen to be there in mid May, the Patio Festival.

The last leg of our journey was a spectacular drive through the mountains to Granada. As we had already visited the Alhambra several years ago we decided to explore the city itself and our first port of call was the Museum (Capilla Real) next door to the Cathedral. There is a beautifully carved tomb in there which contains the remains of Ferdinand, Isabella, two of their children and a grandchild and you can also go down a little set of stairs to view the very unassuming coffins. The Cathedral of the Incarnation was next and it is surprisingly light inside due to the very pale stone that was used to build it. Other places to visit include the Albayzin (old Moorish Quarter), Basilica de Nuestra Senora de las Angustias and, if, like us, you love tapas, Calle Navas.

The drive time to Cordoba was 2 1/2 - 3hrs and to Granada 4 - 4 1/2hrs down motorways and dual carriage ways with very light traffic and plenty of places to stop off for refreshments.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay.

The protestors had demanded the cessation of open-air calcination, a system of burning-off sulphur from heaps of ore in order to extract copper. The smoke produced contained sulphur, arsenic and other dangerous minerals, which choked people and animals and attacked lungs. Vegetation and agricultural crops were destroyed, turning a widespread area into treeless wasteland. Annual indemnities paid to farmers did not ameliorate their opposition and an Anti-Smoke League was formed in Huelva. Reduced visibility also resulted in fatal accidents and in miners being laid off work on half pay. Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

Against a backdrop of national political instability and a strong, active anarchist presence in Rio Tinto, however, there was industrial unrest. A combination of open cast mining, which exposed workers to extremes of weather, and the ever-present danger of serious accidents and sudden death increased worker volatility.

Now there is silence. A green mantle covers the once widely disfigured landscape but the scars left behind are dramatic and strangely beautiful. Huge open pits expose inners of greens, blues, greys, browns and reds. And the craters, with their darkly polluted waters, are streaked in a myriad of wonderfully startling patterns.

Now there is silence. A green mantle covers the once widely disfigured landscape but the scars left behind are dramatic and strangely beautiful. Huge open pits expose inners of greens, blues, greys, browns and reds. And the craters, with their darkly polluted waters, are streaked in a myriad of wonderfully startling patterns. Two new communities at the Tharsis and La Zarza mines and a smaller settlement at the railway terminal and pier in Corrales were created with a total population of about 8000 men, women and children. The 50 or so British managers, mostly Scots raised in the self-help Presbyterian tradition, enforced strict discipline and represented a culture that was alien to that of the traditional, catholic and largely illiterate workforce. A colonial style segregation and paternalism intensified the company's difficulties in an increasingly volatile environment.

Two new communities at the Tharsis and La Zarza mines and a smaller settlement at the railway terminal and pier in Corrales were created with a total population of about 8000 men, women and children. The 50 or so British managers, mostly Scots raised in the self-help Presbyterian tradition, enforced strict discipline and represented a culture that was alien to that of the traditional, catholic and largely illiterate workforce. A colonial style segregation and paternalism intensified the company's difficulties in an increasingly volatile environment. Stretches of the company's railway track between the mines and Corrales remain intact. In Corrales the pier is in a dangerous state of collapse. Its junction box/control tower still stands but it is dilapidated and inaccessible. Of the terminal with its railway tracks, yards, workshops, garage, stores, crushing plants and civil guards' barracks, only a crumbling building with its chimneystack and the railway station survive.

Stretches of the company's railway track between the mines and Corrales remain intact. In Corrales the pier is in a dangerous state of collapse. Its junction box/control tower still stands but it is dilapidated and inaccessible. Of the terminal with its railway tracks, yards, workshops, garage, stores, crushing plants and civil guards' barracks, only a crumbling building with its chimneystack and the railway station survive.

Spanish cartoons reflected the image, one describing him as ‘su majestad Riotinto’ (his Rio Tinto Majesty) and depicting him as a giant with two pygmies, the prime minister and a judge, in tow. Characterised by an explosive energy, he was also known as ‘el terremoto’ (the earthquake) and admired as ‘mucho hombre’ (all man) out of respect for his skilled horsemanship and iron will.

Spanish cartoons reflected the image, one describing him as ‘su majestad Riotinto’ (his Rio Tinto Majesty) and depicting him as a giant with two pygmies, the prime minister and a judge, in tow. Characterised by an explosive energy, he was also known as ‘el terremoto’ (the earthquake) and admired as ‘mucho hombre’ (all man) out of respect for his skilled horsemanship and iron will.

In 1954 the Rio Tinto Company was sold to Compañia Española de Minas de Rio-Tinto SA, a Spanish consortium. Today the Riotinto mines have ceased production but the brooding stillness of a haunting landscape still evokes a sense of wonder at the vastness of Browning’s ‘kingdom’.

In 1954 the Rio Tinto Company was sold to Compañia Española de Minas de Rio-Tinto SA, a Spanish consortium. Today the Riotinto mines have ceased production but the brooding stillness of a haunting landscape still evokes a sense of wonder at the vastness of Browning’s ‘kingdom’.

The spring flowers are just starting to put on their annual display. The first sign of spring is the Bermuda Buttercup, patches of bright yellow in unexpected corners. The almond blossom came very early this year and is now over. But you cannot fail to notice the delicate white flowers of the cistus or rockrose, but try not to get too close to the waxy leaves. The aromatic resin from the leaves is used by the perfumery industry. Asphodels are just coming into their prime and look closer for wild irises and both purple and yellow lupins.

The spring flowers are just starting to put on their annual display. The first sign of spring is the Bermuda Buttercup, patches of bright yellow in unexpected corners. The almond blossom came very early this year and is now over. But you cannot fail to notice the delicate white flowers of the cistus or rockrose, but try not to get too close to the waxy leaves. The aromatic resin from the leaves is used by the perfumery industry. Asphodels are just coming into their prime and look closer for wild irises and both purple and yellow lupins.

The first leg of the trip (Ayamonte to Sevilla) I have made several times but I never cease to enjoy the landscape. It begins with Umbrella Pines, Orange Groves and fields of Strawberries, then as you near Sevilla it changes to Olive Groves. Apart from the obvious detours you can also make en route there are a couple of items I have found particularly interesting. The first is the Ines Rosales Factory. In 1910 Ines Rosales began making tortas de aceite by hand and selling them at the railway station. Unable to keep up with demand she employed local women to help make them and today they are still made by hand using the same recipe and then individually wrapped. They are delicious on there own or with accompaniments such as cheese and fig spread. The second item is the Solar Power Station (known as PS10) which is situated just after the Mercadona Distribution Centre.

The first leg of the trip (Ayamonte to Sevilla) I have made several times but I never cease to enjoy the landscape. It begins with Umbrella Pines, Orange Groves and fields of Strawberries, then as you near Sevilla it changes to Olive Groves. Apart from the obvious detours you can also make en route there are a couple of items I have found particularly interesting. The first is the Ines Rosales Factory. In 1910 Ines Rosales began making tortas de aceite by hand and selling them at the railway station. Unable to keep up with demand she employed local women to help make them and today they are still made by hand using the same recipe and then individually wrapped. They are delicious on there own or with accompaniments such as cheese and fig spread. The second item is the Solar Power Station (known as PS10) which is situated just after the Mercadona Distribution Centre.